Why MBTI Won’t Die

At this point, it feels almost obligatory to preface any mention of MBTI with an apology. It’s debunked. It’s oversimplified. It’s the astrology of Instagram bios and dating apps. Serious students of Jung are expected to roll their eyes on cue, lest they be mistaken for someone who thinks four letters can explain a psyche.

And yet, MBTI refuses to go away.

Not only that—it resurfaces cyclically, often with renewed intensity, crossing platforms, languages, and cultures with a persistence that should probably make us more curious than dismissive. Whatever its scientific shortcomings (and there are many), the typology clearly answers to something real: a desire for orientation, for shared language, for a way to talk about difference without immediately moralizing it.

Jung himself was wary of typology becoming destiny. Types, for him, were provisional descriptions—snapshots of psychic orientation, not portraits of identity. Individuation was always the point: a lifelong process of integrating opposing tendencies, not settling comfortably into coherence. That his name has become most closely associated with a system promising quick “size-ups” is not just a misunderstanding; it’s a cultural symptom.

What interests me is how differently this symptom presents depending on context. In Anglophone spaces, MBTI is often treated as an identity claim—something you are, something that explains your limits, preferences, and even your moral temperament. In South Korea, by contrast, MBTI functions more like social shorthand: a conversational tool, often playful, that opens interaction rather than closing it. Neither use is especially faithful to Jung. But they reveal very different assumptions about what a self is supposed to be.

Pop culture, it turns out, teaches these assumptions remarkably well.

Jung Was Never Just a Typologist

One of the persistent ironies of Jung’s afterlife is that he is best known for the part of his work he treated most cautiously. Jung did write about psychological types, but he never mistook them for the psyche itself. Typology was descriptive, secondary, and explicitly subordinate to individuation—the slow, often uncomfortable integration of opposites within the personality.

This distinction is easy to miss in contemporary discourse, where personality language is expected to explain rather than orient. Typology offers clarity. Individuation demands confrontation. The former is legible and social; the latter is private, nonlinear, and resistant to summary. It is much easier to say “I’m an INFJ” than to ask what remains disowned, projected, or split off in the process of becoming intelligible to others.

Jung’s engagement with Eastern philosophy makes this even clearer. His borrowings from Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucian thought were not decorative. They allowed him to articulate a psyche defined by balance rather than dominance, process rather than endpoint. The self, in this framework, is not a static unit but a field of tension—one that cannot be resolved through categorization alone.

This makes contemporary accusations that non-Western MBTI cultures “misunderstand Jung” feel oddly ahistorical. Jung’s theory has always been hybrid. Its retranslation into East Asian contexts is not dilution so much as recursion. What changes is not the availability of typology, but the cultural work it is asked to perform.

Sherlock: Jung as Pathology and Exceptional Intellect

The BBC’s Sherlock offers a familiar Anglophone translation of Jung: depth as pathology, individuation as isolation, intellect as both wound and justification. Sherlock Holmes is not merely intelligent; he is alienated by intelligence. Emotional distance functions as proof of depth rather than a dimension to be integrated.

Here, Jungian language becomes aesthetic rather than developmental. The shadow is not an invitation to reconciliation, but a source of volatility that confirms brilliance. Affect is interference. Growth, when it occurs, is partial and exceptional, not ordinary or ongoing.

This framing extended easily into fandom culture. To understand Sherlock was to signal seriousness. Jungian vocabulary became a marker of sophistication, a way of aestheticizing detachment. Depth was something one had, not something one practiced.

Benedict Cumberbatch’s public persona reinforced this logic. Intelligent, articulate, emotionally reserved, and carefully distant, he embodied an Anglophone ideal of authority secured through opacity. This is not a moral critique, but a cultural observation. Intellect here is staged through separation.

What emerges is Jung as a language of exception—psychology as destiny rather than process.

BTS: Jung as Process, Affect, and Relation

BTS offers a striking counterpoint. Their engagement with Jung—particularly in the Love Yourself and Map of the Soul eras—treats psychological concepts as experiential states rather than diagnostic labels. Persona, shadow, and ego are not explanations; they are movements in time.

Affect is not interference here, but evidence of depth. Vulnerability does not undermine seriousness; it constitutes it. Individuation unfolds relationally, in dialogue with others, rather than through withdrawal. The psyche is not purified by isolation, but clarified through encounter.

RM provides an especially instructive contrast to Cumberbatch. Both are visibly intelligent, articulate, and philosophically inclined. But where Anglophone authority is often preserved through distance, RM’s authority is built through disclosure. His thinking is presented as tentative, revised publicly, and held with humility.

The result is a different pedagogy of depth. Jung becomes a shared language for navigating interiority rather than a credential to be displayed. Fans are invited not to admire brilliance from afar, but to recognize themselves in motion.

MBTI in Korea and the Anglophone World: Translation, Not Ignorance

These differences reappear at the level of everyday personality discourse. In Anglophone contexts, MBTI is frequently identity-driven and diagnostic. Types explain limits, justify preferences, and quietly accrue moral weight. Certain configurations are valorized; others are pathologized.

In South Korea, MBTI functions more relationally. It appears as shorthand, conversation starter, and social lubricant—often explicitly playful. Rather than foreclosing inquiry, it opens it. The type is not destiny; it is context.

Western critiques often focus on the absence of “proper” cognitive-function discourse in Korean MBTI culture, overlooking the irony that Jung himself drew heavily from East Asian traditions. The insistence on a single correct interpretation reveals an assumption that psychology exists primarily to define individuals rather than orient relationships.

MBTI’s persistence, then, looks less like confusion than adaptation.

MBTI in K-Pop: Personality as Pop Pedagogy

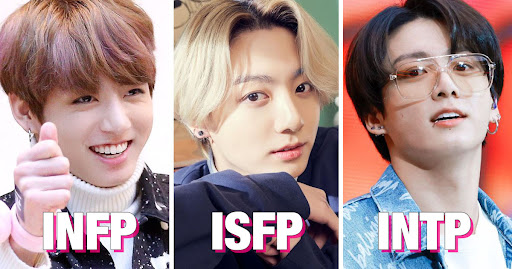

Once MBTI enters K-pop explicitly—through lyrics, concepts, and self-conscious performance—it becomes pedagogy. Types function as moods, relational expectations, and symbolic shorthand rather than diagnoses.

BTS’ repeated retaking of the MBTI test illustrates this beautifully. Results shift. Ambiguity remains unresolved. Jungkook’s offhand wish to be a different type is playful rather than distressed. Typology is treated freely—revisable, and non-fateful.

This ambiguity sustains multiple readings. Western fans often approach the material diagnostically, insisting on a “true” type. Korean fans are more likely to treat it as social play. The same gesture supports both interpretations. The openness is not accidental; it is the mechanism.

Jung, filtered through this loop, survives not intact but usable.

Fandom + Projection + “Intellectualism” Anxiety

Where personality language circulates widely, projection follows. Symbols attract meaning. Fandoms organize it.

The anxiety around “intellectual fangirls” reveals less about Jung than about authority. Who gets to claim depth? Who gets to play with symbolic language without being policed? The charge of superficiality often masks a desire to control meaning rather than clarify it.

The real danger is not popularization, but freezing. When typology becomes destiny, growth stops. When it becomes aesthetic only, depth evaporates. Jung walked a narrow path between structure and fluidity. Pop culture, for all its distortions, sometimes preserves that tension better than its critics.

Conclusion: Individuation Is Not a Typing Exercise

If Jung keeps returning in simplified form—through MBTI, pop music, prestige television—it is not because his ideas are shallow, but because they are unfinished. Jung never offered a system that could be mastered and put away. He offered a way of thinking that resists closure: a psychology concerned less with naming the self than with encountering it, again and again, under changing conditions.

What pop culture reveals, at its best, is not Jung’s dilution but his durability. Sherlock shows us what happens when individuation is misread as exceptional intellect and emotional distance. BTS, by contrast, gestures toward individuation as process—affective, relational, revisable. MBTI, circulating between these interpretations, becomes a cultural symptom rather than a diagnostic tool: a language people reach for when they want orientation without foreclosure.

The mistake is not in using typology, but in mistaking it for truth. Personality language can open inquiry or arrest it. It can orient us toward difference or harden into identity. Jung warned against the latter not because he distrusted structure, but because he understood how easily it becomes a refuge from transformation.

To study Jung seriously today is not to defend him from popularization, but to notice what popularization reveals: a widespread hunger for symbolic language, for process over certainty, for ways of speaking about the psyche that do not collapse it into either pathology or performance. Individuation, after all, was never meant to be typed. It was meant to be lived.

Featured images courtesy of production company/label (edited by blog author) + body images credits to their photographer/company (original edit of BTS member belongs to the fan site Koreaboo).

Leave a comment